I have not been able to find any evidence that James and Henry Ford had relatives in Jamaica England Highgate Cemetery

By chance, I found that the youngest daughter, Jessy Maria, came to Kingston Jamaica

Family history research is more than just records of birth, marriage and death. We want to know more than just the bare facts about our ancestors –what they were like and how they lived. Without access to such materials as letters or diaries we have to depend on other sources, and one such is the local newspaper. Jamaican researchers are fortunate to have access to the online Jamaica Gleaner, a subscription website. Thanks to the Gleaner online I found several references to both James and Henry Ford and how they had prospered in Jamaica Jamaica St. Thomas Australia , returning to Jamaica

James’s obituary, unfortunately, was not as extensive. He died as a result of malarial fever in 1881, at age 56. The following brief notice appeared in the Gleaner of 16 June, 1881:

With deep regret we announce the death of Mr. James D. Ford, at his residence in Duke Street , at 3 o'clock this morning. Mr. Ford had been ill only a few days from malarial fever, but his strength gave way speedily. He was 53 [sic] years of age and at the time of death head of the Good Templars of Jamaica. We have been requested to state that in consequence of his death the Congregational Lodge, I.O.G.T., will not meet this evening. The funeral takes place at 5 p.m. today.

Nothing about his business endeavours or even his family! No doubt the obituary was written by a Masonic brother! Fortunately I found other items about James in the Gleaner. I knew from his marriage record that he was a bank clerk when he married Cordelia Henriques. He must have been incredibly industrious as he rose from that position to that of auditor for both the Jamaica Co-Operative Fire Insurance Company and the Jamaica Marine Insurance Company.

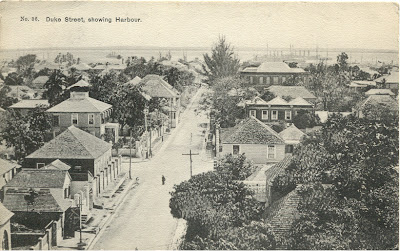

The advertisements appeared in the Gleaner in 1879. But other notices about James’s business endeavours were even more interesting. Along with his auditor’s work James ran a school at his home in Duke Street, the Kingston University School. It opened on 2 October 1871 and was described in the first advertisements as offering “a sound, practical and liberal education, based upon high moral and intellectual principles.”

The following is an example of one of the advertisements from the Gleaner of 12 November, 1872.

I was particularly intrigued by the mention of Hebrew as an extra subject. Did Cordelia help teach that course, or did James hire a Jewish acquaintance to teach the language? Another interesting point is that the school took boarders, which means James’s house at 118 Duke Street must have been quite large. Duke Street would have been quite an attractive neighbourhood to live in, and a sign that James had indeed done quite well for himself.

The purpose of the school seems to have been to prepare young men for the professions, judging by the following advertisement in the Gleaner of 10 June, 1878:

Less than three years later James was dead and one wonders what happened to the school. Cordelia outlived him by a mere seven months. Perhaps Henry took over the operation of the school. According to an advertisement in the Gleaner of January 27, 1902, he had been living at 118 Duke Street when he died and creditors of the estate were instructed to send their claims to his wife. However, I could find no further references to the school in the Gleaner after James’s death and it appears that 118 Duke Street must have been sold and eventually converted to apartments.

James and Henry are examples of immigrants to Jamaica who did very well both in business and in life. Both married and had families. James and his wife, Cordelia Henriques, had ten children. Henry married Ellen Hannah Savage and they had one daughter, Edith. One of James’s sons, Edmund George, settled in Panama and raised a family there. My research into this branch of the Cunha family has been a fascinating one.

.jpg)